A Short History of EAB in the United States

It’s been national news since it was first detected in a suburb of Detroit, Michigan in 2002. Emerald ash borer is a highly invasive insect that has killed millions of trees since its accidental introduction from Asia. In Nebraska, it has been comfirmed in several locations in eastern parts of the state and as far west as Kearney.

All ash species are susceptible, including white, green and black ash. European mountain ash and wafer ash are not affected by EAB, because despite their common names they are not true members of the ash family. Popular ash cultivars ‘Autumn Purple’, ‘Marshall’s Seedless’ and ‘Patmore’ are true members of the ash family and are susceptible.

Ash trees can be identified by several unique characteristics. All have compound leaves, typically with 5-11 leaflets. Edges of the leaflets can be either toothed or smooth. Ash trees have an opposite branching pattern, with leaves developing opposite each other on the stem. Ash seeds are flat, narrow elongated ovals and develop in drooping clusters.

Ash Tree Identification Guide, Nebraska Forest Service

Identification

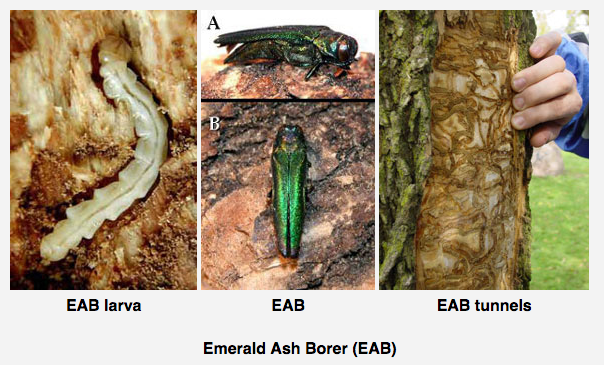

Adult beetles are small, only about ½ inch long, long and slender and metallic green in color. They emerge from infested trees in early summer, June and July. Adult females lay eggs in the bark of branches or the main trunk.

Adult beetles are small, only about ½ inch long, long and slender and metallic green in color. They emerge from infested trees in early summer, June and July. Adult females lay eggs in the bark of branches or the main trunk.

Larvae are borers and tunnel just under the bark after hatching. They are flat, cream-colored and legless. They have a brown head, and their bodies are divided into 10 segments, which are bell-shaped near the back end of the insect. At maturity, they reach 1½ inches in length. After pupating into adults, the beetles chew their way out of the tree, leaving behind a D-shaped hole.

Symptoms

EAB attacks healthy trees, with eggs laid in the upper twigs, secondary branches, and main trunk. One of the first symptoms seen in affected trees is branch dieback in the top 1/3 of a tree. As the infestation progresses, trees often respond by sending up suckers, or adventitious branches, from the base.

EAB attacks healthy trees, with eggs laid in the upper twigs, secondary branches, and main trunk. One of the first symptoms seen in affected trees is branch dieback in the top 1/3 of a tree. As the infestation progresses, trees often respond by sending up suckers, or adventitious branches, from the base.

Inspect trees for the presence of D-shaped holes. The exit holes are small, only about 1/8 inch across.

As insect tunneling occurs under the bark, sections of bark die and often crack. These cracks will occur vertically, or up and down the trunk, over a dead bark section. Woodpeckers are often attracted to infested trees, and peck into the bark in search of borer larvae. So woodpecker damage in an ash tree could also point to a developing EAB infestation.

Trees under attack by EAB do not die immediately. Healthy trees use their resources to kill as many of the invading immature borers as possible. Typically symptoms of branch dieback don't become obvious until the tree has been infested for three or more years, so there is time to treat infested trees once symptoms are noticed.

15-Mile Treatment Consideration Zone

The Nebraska Forest Service recommends not beginning to treat your trees until your property is within 15 miles of an EAB confirmed site. The 15-mile recommendation strikes a balance between protecting valuable trees and limiting the negative effects of unnecessary treatments.

Injection and implant insecticide applications provide the best control in large trees, those 45-inch circumference and over (measured at 4 feet above the ground), but they do have drawbacks - specifically they cause damage to the tree. Most are applied by drilling holes into the tree’s trunk, which opens up the trunk to insect pests and decay fungi. Drilling may also break through internal barriers, created by the tree within the trunk, to wall off internal decay. Breaking this barrier allows decay to spread into healthy wood. In addition, the pesticide itself can cause internal damage that may accumulate over years of repeated injections and potentially kill the tree, even if the pest is controlled.

Treating trees outside of the 15-mile zone provides little or no benefit to trees, yet exposes humans and the environment to pesticides, wastes money and, in the case of trunk injections, causes unjustified tree damage.

Control

First, determine if the problem with your tree is really EAB. If a tree is dying or diseased, contact a certified arborist or professional to determine whether the symptoms are due to EAB or other problems. Resources to help you find a certified arborist are below.

As mentioned earlier, EAB does not kill trees quickly; it takes a few years of continued infestation before trees begin to decline. Often insects have been in a tree for 2-3 years before signs of decline are noticed and 1-2 more years before the tree dies completely.

If homeowners begin to treat their trees when 30% or less canopy dieback has occurred, an otherwise healthy vigorous tree can usually be expected to fully recover. Trees with over 50% canopy dieback, however, are less likely to recover.

So even if, in the worst-case scenario, your tree is found to have EAB this summer there is plenty of time to begin treating and have the tree make a good recovery.

What is the Best Time of Year to Treat?

Trees take in the systemic insecticides used against EAB best from April through early June. Research has shown that fall applications, although discussed on some product labels and promoted by some tree care companies, require double the amount of product be used to provide the same level of control as spring applications.

Considering the slow-moving nature of EAB, waiting until spring is the best choice – offering a balance between protecting the tree and preventing the introduction of extra insecticide in the environment.

So stay calm and take your time. Don’t be in a hurry to treat your trees.

For more information, take a look at these publications.

- EAB: Frequently Asked Questions, Nebraska Forest Service

- Selecting Trees for Emerald Ash Borer Treatments, Nebraska Forest Service

- Emerald Ash Borer Trunk Injection Treatment Options for Professionals , Nebraska Forest Service

- Nebraska Forest Service EAB website

6/30/2020